One animal that has adapted exceptionally well to the human environment is the Virginia Opossum (Didelphis virginiana). This magnificent marsupial is native to Central America and the southeastern United States. In the 1890s, they were introduced and now thrive along the West Coast. In nature, they live in shrublands and grasslands, but prefer woodlands and thickets near a water source. They now also live among humans in cities and suburbs. Opossums take shelter in the burrows of other animals, tree cavities, brush piles, and under houses or decks.

One animal that has adapted exceptionally well to the human environment is the Virginia Opossum (Didelphis virginiana). This magnificent marsupial is native to Central America and the southeastern United States. In the 1890s, they were introduced and now thrive along the West Coast. In nature, they live in shrublands and grasslands, but prefer woodlands and thickets near a water source. They now also live among humans in cities and suburbs. Opossums take shelter in the burrows of other animals, tree cavities, brush piles, and under houses or decks.

The opossum is the only marsupial in North America. Marsupials are a group of mammals such as kangaroos and koalas that have pouches for their young, called joeys. As many as 13 opossum joeys nurse in the pouch for up to six weeks before climbing onto their mother’s back, where they will hold on for four or five more months. The opossum is an omnivorous generalist, meaning they will essentially consume anything edible, including fruits, plants, insects, small animals, carrion (dead animals), nuts, seeds, and human food waste. Opossums have 50 teeth, more than any other North American land mammal. Just as with humans, the variance among pointed, sharp, and grinding teeth allow opossums to rip, bite, and chew different foods. Being a generalist is often beneficial when living near humans and other animals. It reduces the need for hunting and conflicts from competition. Scavenging allows opossums to eat without having to expend a lot of energy. Eating deceased animals also helps humans and other wildlife by eliminating rotting flesh that could spread disease.

Opossums are incredible climbers, thanks to several adaptations. Their tail is prehensile, meaning they have complete control of it, using it like a fifth hand. Opossums will use their tail to carry sticks or food, wave it as a distress signal to other opossums, and will wrap it around a tree or branch for stability. Similar to how a snake wraps around an object, the opossum’s tail coils around a branch as a safety line and fifth point of balance. While joeys can hang upside down for short periods, adults are unable to. Opossums have another amazing adaptation on their hind legs. They have an opposable toe, like the human thumb, on each back foot, which allows for a stronger grasp when climbing. With these adaptations, opossums can climb and traverse with ease in arboreal and human-built environments.

Opossums are incredible climbers, thanks to several adaptations. Their tail is prehensile, meaning they have complete control of it, using it like a fifth hand. Opossums will use their tail to carry sticks or food, wave it as a distress signal to other opossums, and will wrap it around a tree or branch for stability. Similar to how a snake wraps around an object, the opossum’s tail coils around a branch as a safety line and fifth point of balance. While joeys can hang upside down for short periods, adults are unable to. Opossums have another amazing adaptation on their hind legs. They have an opposable toe, like the human thumb, on each back foot, which allows for a stronger grasp when climbing. With these adaptations, opossums can climb and traverse with ease in arboreal and human-built environments.

In urban environments, opossums’ main threats come from humans and cars. When approached by oncoming traffic, they often respond by “playing possum,” an automatic fear response that forces an opossum’s body to go limp and appear dead. In the wild, this reaction can safeguard them from predators who prefer hunting live prey. Release of unpleasant secretions from scent glands while “playing dead” can also be a powerful deterrent. However, in the face of a fast-moving vehicle, this response is highly ineffective and often results in serious injury or death to the opossum. The Virginia Opossum is currently classified as a species of ‘Least Concern’ on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, which means opossums are not considered threatened or endangered. As with all wildlife, they remain important to respect and protect. Opossums offer valuable services by eating carrion and pests, soil tilling, seed spreading, and pollination. When driving at night, use headlights and be aware of our furry friends.

The Northern river otter (Lontra canadensis) is a semi-aquatic mammal, adapted for life both on land and in water. Northern river otters inhabit saltwater and freshwater streams, rivers, lakes, ponds, and marshes throughout much of the United States and Canada, preferring areas with minimal human activity. They establish narrow underwater burrows to access their dens, allowing them to escape from large predators like bobcats, alligators, coyotes, and raptors.

The river otter’s thick, water-repellent fur helps to protect them in cold water. Their coat is brown or gray with a lighter underbelly. Short legs and fully webbed feet allow them to swim with speed, while their long, streamlined bodies and flattened heads make them agile in the water. Their strong, flexible tails propel them through the water, allowing them to swim up to 8 miles per hour – four times faster than an average human swimmer. Their eyes and ears are located high on their head so they can see and hear while surface swimming, and a third eyelid protects their eyes and allows them to see when swimming underwater. River otters use long whiskers to locate their prey – mostly fish – in dark or cloudy water.

Ad ult river otters are 36-48 inches long, including their tail, and weigh 15-35 pounds. River otters live alone, in pairs, in small groups of males, or in family groups typically made up of a female otter and her young. Litters usually consist of two or three pups, each weighing about five ounces, born in March or April. Otter pups are born with fur, open their eyes roughly four weeks later, and begin to swim under the close watch of their mother at the age of two months. The pups are weaned at three or four months but generally stay with their mother as a family unit for several months longer. Their playful behavior strengthens social bonds and helps them learn hunting and survival techniques. Otters communicate with a variety of vocalizations, including whistles, chirps, and growls, as well as through scent marking.

ult river otters are 36-48 inches long, including their tail, and weigh 15-35 pounds. River otters live alone, in pairs, in small groups of males, or in family groups typically made up of a female otter and her young. Litters usually consist of two or three pups, each weighing about five ounces, born in March or April. Otter pups are born with fur, open their eyes roughly four weeks later, and begin to swim under the close watch of their mother at the age of two months. The pups are weaned at three or four months but generally stay with their mother as a family unit for several months longer. Their playful behavior strengthens social bonds and helps them learn hunting and survival techniques. Otters communicate with a variety of vocalizations, including whistles, chirps, and growls, as well as through scent marking.

Excessive hunting of river otters for their fur in the 19th and 20th centuries decimated populations in parts of their range. Since that time, river otter numbers have stabilized, and they are now a species of Least Concern (LC) under the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). In the Bay Area, numbers have increased due to conservation and restoration activities following the Clean Water Act of 1972. However, habitat destruction and water pollution still put these animals at significant risk. Because river otters are an indicator species, whose presence reflects the health of a particular ecosystem, the information we gather about their populations is essential to gauging the health of our waterways.

This American Bittern is a fantastic specimen from Lindsay’s natural history collection. American Bitterns inhabit wetlands, preferring freshwater areas, especially during their breeding season. This strange-looking bird has several adaptations that help it thrive in wetland habitats.

This American Bittern is a fantastic specimen from Lindsay’s natural history collection. American Bitterns inhabit wetlands, preferring freshwater areas, especially during their breeding season. This strange-looking bird has several adaptations that help it thrive in wetland habitats.

Bitterns are known for their brown-colored feathers, white streaks, and long neck, all characteristics that make Bitterns masters of camouflage. By extending their neck and standing perfectly still, they can blend in with the grasses and plants of their wetland habitats. This specimen’s posture is a perfect example of how a Bittern would look when attempting to hide from predators.

American Bitterns are slow-moving creatures, generally staying within reeds and grass to help them hide not only from predators but also remain undetected by their own prey. American Bitterns are stealthy hunters, standing incredibly still and quickly grabbing prey with their beak. They’re not too picky when it comes to their meal and will typically eat any small creature they find, including small fish, eels, small snakes, salamanders, insects, frogs, crayfish, and small mammals. Their downward-facing eyes are an adaptation that allows them to spot prey in the water or grass below them without moving, making them excellent hunters.

While their camouflage makes it difficult to spot American Bitterns in the wild, their incredible mating call may help in locating them. The male’s mating call sounds like a gulp followed by a water-dripping noise, which is repeated up to 10 times and can be heard from some distance. The male creates this bizarre sound by inflating his esophagus, contorting his body, and opening and closing his bill. The female responds with similar calls that are much quieter. Outside of breeding season, American Bitterns are solitary creatures. American Bitterns are prone to the negative effects of habitat loss. City development and expansion have caused a large reduction in our wetlands, with as much as 90% of California’s original wetland space no longer in existence. Due to the decrease in freshwater wetlands, American Bittern populations are rapidly declining. As California gets more than two-thirds of its drinking water from wetlands, habitat loss is a major problem not only for our wetland inhabitants but for us as well. Understanding where our water comes from and conserving water whenever possible can help preserve what’s left of our precious wetland habitats.

From saran-wrapping logs to airbrushing artificial ferns, fabricating a diorama at Lindsay Wildlife Experience is no easy task. But the education team had a vision: to transport visitors into the coastal redwoods to deepen their connection to this diverse and delicate ecosystem —and learn about some of its inhabitants.

From saran-wrapping logs to airbrushing artificial ferns, fabricating a diorama at Lindsay Wildlife Experience is no easy task. But the education team had a vision: to transport visitors into the coastal redwoods to deepen their connection to this diverse and delicate ecosystem —and learn about some of its inhabitants.

Determining the scene was easy, as most people connect with their local redwoods through trails. However, not everyone gets to see the more elusive wildlife that calls this ecosystem home. To highlight these animals, the scene was set at dusk when many crepuscular animals come out from hiding to forage or hunt for food. Natural history specimens from the museum’s extensive collection were selected, and the layout was created using a model of the exhibit space. To inspire interaction with guests, elements of discovery were placed in the diorama to highlight the natural behaviors of each animal.

Determining the scene was easy, as most people connect with their local redwoods through trails. However, not everyone gets to see the more elusive wildlife that calls this ecosystem home. To highlight these animals, the scene was set at dusk when many crepuscular animals come out from hiding to forage or hunt for food. Natural history specimens from the museum’s extensive collection were selected, and the layout was created using a model of the exhibit space. To inspire interaction with guests, elements of discovery were placed in the diorama to highlight the natural behaviors of each animal.

Once the scene was composed, the team began work on the foreground. Expanding polyurethane foam was poured into place on a thin wooden base to create a foundation. Using some creative problem solving, the fallen redwood log was saran wrapped and put in place before foam was poured around it to stabilize the object. Real redwood dirt and debris were ‘cleaned’ through freezing and sifting, and adhered to the foam foreground with spray adhesive. After many layers of dirt and debris were set, it was time to create the backdrop and foreground elements.

Once the scene was composed, the team began work on the foreground. Expanding polyurethane foam was poured into place on a thin wooden base to create a foundation. Using some creative problem solving, the fallen redwood log was saran wrapped and put in place before foam was poured around it to stabilize the object. Real redwood dirt and debris were ‘cleaned’ through freezing and sifting, and adhered to the foam foreground with spray adhesive. After many layers of dirt and debris were set, it was time to create the backdrop and foreground elements.

The backdrop was painted on two large pieces of canvas that overlap in the back to provide access to the exhibition space. Once the large trees and ground were painted, the fog was airbrushed to create the illusion of atmospheric depth and the dewy essence of the coastal redwoods. Faux ferns were airbrushed a brighter green to match our local ferns, and a volunteer fabricated two types of fungus and a banana slug representing species not in the museum’s Natural History collection. Once all of the foreground elements were complete, small holes were drilled into the foam to stabilize each object. An interpretive sign with a map and specimen labels illustrated by Lindsay volunteer Mimi Foord invites guests to explore the diorama.

The backdrop was painted on two large pieces of canvas that overlap in the back to provide access to the exhibition space. Once the large trees and ground were painted, the fog was airbrushed to create the illusion of atmospheric depth and the dewy essence of the coastal redwoods. Faux ferns were airbrushed a brighter green to match our local ferns, and a volunteer fabricated two types of fungus and a banana slug representing species not in the museum’s Natural History collection. Once all of the foreground elements were complete, small holes were drilled into the foam to stabilize each object. An interpretive sign with a map and specimen labels illustrated by Lindsay volunteer Mimi Foord invites guests to explore the diorama.

Come by our exhibit hall to check out the Coastal Redwoods diorama and see what connections you can make with your local redwood ecosystem.

Lindsay’s natural history collection has over 16,000 specimens, not least of which is this jaunty little mole. Moles are in the order Eulipotyphla, meaning “truly fat and blind” (not very flattering!), and the family Talpidae, meaning, appropriately, “mole.” Those found in California are called broad-footed moles, but moles can live just about anywhere. They’re found on every continent except Antarctica, and can thrive in many different types of environments as long as there’s dirt to dig in!

Lindsay’s natural history collection has over 16,000 specimens, not least of which is this jaunty little mole. Moles are in the order Eulipotyphla, meaning “truly fat and blind” (not very flattering!), and the family Talpidae, meaning, appropriately, “mole.” Those found in California are called broad-footed moles, but moles can live just about anywhere. They’re found on every continent except Antarctica, and can thrive in many different types of environments as long as there’s dirt to dig in!

Moles live almost exclusively underground, and are well known to gardeners and landscapers for their tendency to burrow and bulldoze their way through nicely manicured lawns. Animals that spend most of their lives below ground are called fossorial animals; meerkats, badgers, and clams are also fossorial. Because they are adapted to living underground, moles look pretty unusual! Moles have very small eyes and some are almost completely blind as it isn’t very helpful to be able to see well when you’re digging through the ground in the dark. Most moles don’t have external ears because big ears would drag through the dirt and slow them down. However, they do have inner ears and can actually hear very well. Moles have short, reduced hind limbs, but big, powerful forelimbs with large paws. These mammals also have an extra “thumb” on each hand, so they have 12 fingers total. This extra digit evolved to increase the size of their hands and allow them to more quickly scoop dirt.

Moles construct elaborate systems of tunnels, sometimes more than 15 feet below the surface, and they make room for nesting chambers and storage areas, too. All this digging requires a mole to burn a lot of energy. To make up for that lost energy, they have to eat around 70-100% of their body weight in insects each day — that’s like an average-sized adult eating 150 pounds of sandwiches. Moles mainly eat earthworms, so to maintain a healthy weight, a mole has to eat close to 200 worms a day. Some moles are venomous, and can inject worms with a toxin that paralyzes, but doesn’t kill them; moles store these worms in underground “larders.” Some of these larders have been found to contain over 1,000 worms!

Moles construct elaborate systems of tunnels, sometimes more than 15 feet below the surface, and they make room for nesting chambers and storage areas, too. All this digging requires a mole to burn a lot of energy. To make up for that lost energy, they have to eat around 70-100% of their body weight in insects each day — that’s like an average-sized adult eating 150 pounds of sandwiches. Moles mainly eat earthworms, so to maintain a healthy weight, a mole has to eat close to 200 worms a day. Some moles are venomous, and can inject worms with a toxin that paralyzes, but doesn’t kill them; moles store these worms in underground “larders.” Some of these larders have been found to contain over 1,000 worms!

Even though moles are considered pests, they actually perform a number of behaviors that are useful to the ecosystem. For example, by digging through and turning over the soil, moles actually break up clumps of dirt and allow more air into the soil. Aeration stimulates root growth and makes it easier for earthworms to move through the soil, promoting better composting. Moles also eat other garden pests like slugs and grubs, and are eaten in turn by predators like foxes and coyotes; they play an important role in the food web. The biggest threat that moles face are human pest exterminators, so if you find evidence of moles in your yard, try to get rid of them humanely! Plant strong-smelling flowers like daffodils, get rid of food sources like grubs in your yard, or apply a natural mole repellent like castor oil and dish soap to discourage moles. Your yard and the environment will thank you.

One of the fascinating specimens in our natural history collection is this fern (Pecopteris sp.) concretion. Similar to a fossil, a concretion is the preserved impression of a prehistoric organism formed from sediments before they harden into rocks. The genus Pecopteris’ name is derived from the Greek word pekin, meaning to comb, due to the leaflets of Pecopteris’ fronds resembling the teeth of a comb. All ferns are vascular plants meaning that they don’t have seed or flowers but instead reproduce using spores. This specimen is from Illinois and is from the Pennsylvanian Period (323.2 – 298.9 million years ago). Ferns first appeared during the Devonian Period (419.2 – 358.9 million years ago); however, ferns in the genus Pecopteris became extinct in the Permian Period (298.9 – 252.2 million years ago) as a result of the Earth’s temperature dropping and the disappearance of swamps.

One of the fascinating specimens in our natural history collection is this fern (Pecopteris sp.) concretion. Similar to a fossil, a concretion is the preserved impression of a prehistoric organism formed from sediments before they harden into rocks. The genus Pecopteris’ name is derived from the Greek word pekin, meaning to comb, due to the leaflets of Pecopteris’ fronds resembling the teeth of a comb. All ferns are vascular plants meaning that they don’t have seed or flowers but instead reproduce using spores. This specimen is from Illinois and is from the Pennsylvanian Period (323.2 – 298.9 million years ago). Ferns first appeared during the Devonian Period (419.2 – 358.9 million years ago); however, ferns in the genus Pecopteris became extinct in the Permian Period (298.9 – 252.2 million years ago) as a result of the Earth’s temperature dropping and the disappearance of swamps.

The movement of plants to land began during the Ordovician Period (485.4 – 443.8 million years ago), but their domination of terrestrial ecosystems didn’t really begin until the Devonian Period (419.2 – 358.9 million years ago). This time of rapid diversification is known as the Devonian Explosion. These plants began to spread out and began to form Earth’s first forests. Those prehistoric forests dramatically impacted many of Earth’s patterns including erosion rates, the carbon cycle, and the climate. There was also an increase in carbon burial during this period, which led to a decrease in the greenhouse effect and to several global cooling events. These cooling events are one of the proposed reasons for the Late Devonian extinction.

This particular fossil was collected from a coal mine in Illinois. Most of the Earth’s coal and natural gas was created from the carbon burial events that happened during the Age of Ferns (the Carboniferous Period which took place 369-280 million years ago). Therefore, the anthropogenic use of these plant remains — the same plants that caused global cooling and the late Devonian extinction — is a key contributor to global warming today. It is vital that we learn from the Earth’s history and work to find greener sources of energy and fuel. In ensuring that we do not further impact our planet’s climate and weather patterns, we can help sustain life on Earth as we currently know it.

Lindsay’s vast natural history collection includes these American Oystercatcher (Haematopus palliatus) eggs. The American Oystercatcher is commonly referred to as the American pie due to its original name “sea pie.” In 1731, naturalist Mark Catesby renamed the bird from “sea pie,” to “American oystercatchers” after observing the bird eating oysters. Its genus name, Haematopus, is Greek for “blood foot,” which refers to the oystercatcher’s pink legs, and its species name Palliatus means “cloaked,” which refers to the black cloak of feathers on its head.

Lindsay’s vast natural history collection includes these American Oystercatcher (Haematopus palliatus) eggs. The American Oystercatcher is commonly referred to as the American pie due to its original name “sea pie.” In 1731, naturalist Mark Catesby renamed the bird from “sea pie,” to “American oystercatchers” after observing the bird eating oysters. Its genus name, Haematopus, is Greek for “blood foot,” which refers to the oystercatcher’s pink legs, and its species name Palliatus means “cloaked,” which refers to the black cloak of feathers on its head.

As its name suggests, these birds commonly eat mollusks by stabbing their flat bill into partially open shells and severing the muscles that hold the shell together which allows the bird to be able to eat the soft inner parts. The bill is also used as a hammer to open a mollusk’s shell allowing the bird to crack it open. Chicks often have to rely on their parents to feed them because their beaks are not strong enough for them to pry open bivalves until up to 60 days after hatching. However, they are able to run within 24 hours of hatching!

American Oystercatchers can currently be found on the Atlantic coast of North America to New England as well as on the Gulf Coast, the Caribbean, and even South in Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina. Current threats facing American oystercatchers include coastal development, pollution, disease, and invasive species. Due to this species’ loss of natural habitat as well as an increase in predation on more traditional ocean-front habitats, American oystercatchers have started to nest on spoil islands, marshes, and forest edges. The rise in sea level has also eliminated small islands that these birds used for nesting and roosting. By 1900, the American oystercatcher had been pushed out of areas north of Virginia and their remaining historic range—originally the entire Atlantic coast of the United States and the Labrador Peninsula of Canada—as a result of market hunting, egg collecting, and human disturbance. However, thanks to conservation efforts, in 1997 on Cape Sable Island, Nova Scotia in Canada, the first recent oystercatcher nest was confirmed. We can continue to help protect American oystercatchers by staying at least 50 yards away from nesting sites when visiting the beach and by supporting organizations and legislation that help protect this species’ coastal habitat.

This striking specimen is a Horn Coral fossil. Horn Corals refer to any coral within the order Rugosa. Their name is derived from the horn-like and wrinkled appearance of a solitary coral. Although they may not look like it, corals are a part of the kingdom Animalia — they’re animals!

This striking specimen is a Horn Coral fossil. Horn Corals refer to any coral within the order Rugosa. Their name is derived from the horn-like and wrinkled appearance of a solitary coral. Although they may not look like it, corals are a part of the kingdom Animalia — they’re animals!

Horn Corals existed between the Ordovician and Permian periods, a range that began 485.4 million years ago and ended 251.9 million years ago.

They went extinct during the Permian-Triassic extinction event — the largest extinction event to ever occur. This mass extinction, which occurred about a quarter of a billion years ago, wiped out roughly 95% of marine life along with 70% of terrestrial life.

When thinking about corals, people commonly imagine coral reef ecosystem. These reefs are characterized by large colonies of individual coral polyps and the skeletal secretions produced by these polyps. The polyps sit inside stony cups, or calyxes, that they build while growing and catching plankton with the tentacles around their mouths. In addition to the plankton, corals receive nutrients from the zooxanthellae that live inside of them. Zooxanthellae are photosynthetic algae that give the corals their color, produce oxygen as well as sugars, and consume the CO2 produced by the corals. This mutualistic relationship is what drives the growth of coral reefs. Unfortunately, this endosymbiotic relationship is sensitive, and when coral gets stressed, the algae is expelled from the polyps. This process is referred to as coral bleaching. Without the zooxanthellae, the coral turns white and although it can continue to live and potentially recover, the coral will begin to starve and is more prone to disease.

Rising ocean temperatures are one of the largest stress factors causing coral bleaching. Because corals are a keystone species to coral reefs, coral bleaching affects all other species in the ecosystem. Coral reefs provide natural protection to coastlines and provide homes and spawning sites for countless marine species. Without coral reefs, coastline communities along with wildlife would suffer. But there is hope. By working to mitigate climate change and reduce pollutants in the water, coral reefs can begin to thrive once again.

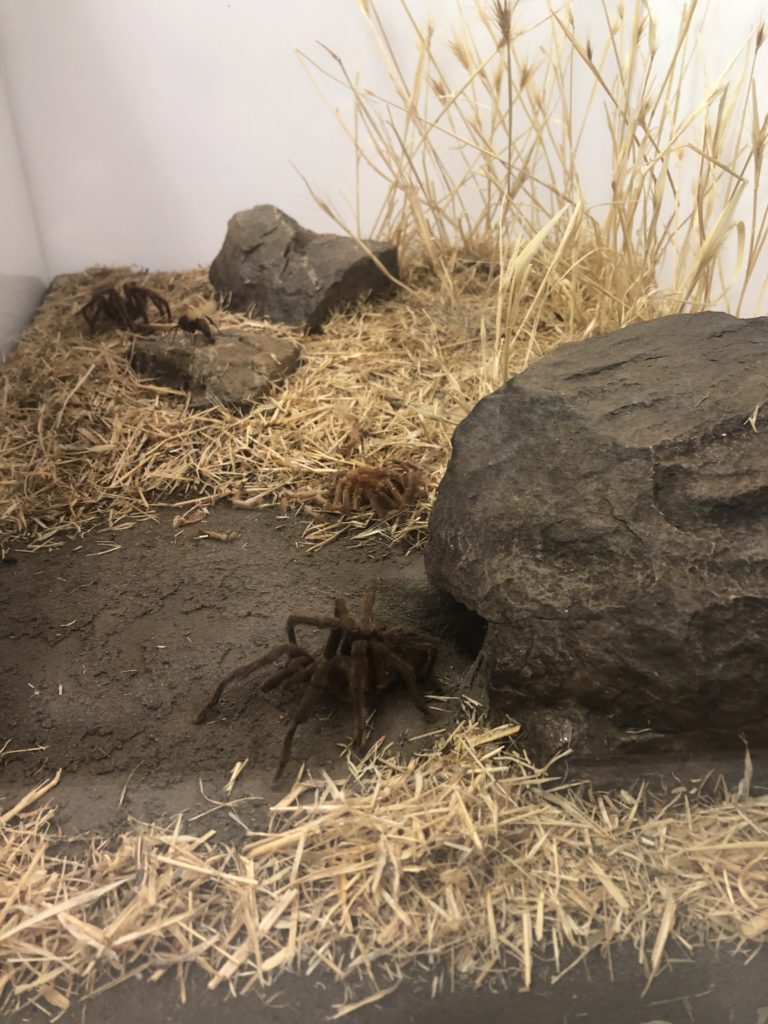

One of the many fascinating objects in our collection is a tarantula (Aphonopelma sp.) diorama. The diorama displays a tarantula exiting its underground burrow with a fresh molt just outside the entrance. On the left side of the scene, a different tarantula is caught in a deadly dance with a female tarantula hawk wasp (Pepsis sp.). The tarantula is North America’s largest spider measuring up to 11 inches in height (including legs). Despite its appearance, the tarantula (Aphonopelma sp.) has very small venom glands containing mild venom that is only strong enough to paralyze small insects. To humans, its bite would feel no more painful than a bee sting.

One of the many fascinating objects in our collection is a tarantula (Aphonopelma sp.) diorama. The diorama displays a tarantula exiting its underground burrow with a fresh molt just outside the entrance. On the left side of the scene, a different tarantula is caught in a deadly dance with a female tarantula hawk wasp (Pepsis sp.). The tarantula is North America’s largest spider measuring up to 11 inches in height (including legs). Despite its appearance, the tarantula (Aphonopelma sp.) has very small venom glands containing mild venom that is only strong enough to paralyze small insects. To humans, its bite would feel no more painful than a bee sting.

Tarantulas are nocturnal and spend most of their lives underground in burrows. Like other spiders, tarantulas shed their external exoskeleton periodically in a process called molting. For young tarantulas, molting occurs several times a year as they grow. The frequency will decrease to roughly once a year or less once maturity is reached. The molting process even also allows these spiders to replace lost appendages and internal organs.

At around 4 to 7 years old, a male tarantula will reach sexual maturity, It will shed its exoskeleton for the last time, develop tibial spurs on its front legs, and will leave its burrow in search of a mate. Locally, mating season takes place from late August through early October, and several males can have been spotted in Mt. Diablo around this time in search of a mate. Once a male has located a female, he will rhythmically tap his pedipalps at the entrance of her burrow similar to knocking on a door. As she approaches, he will then use his newly grown tibial spurs as hooks to clasp the female’s fangs (in order to avoid becoming dinner) and begin mating. Afterwards, the male will scurry off to continue looking for other females to mate with, growing weaker and finally dying as winter approaches. The female, however, will live for around 20 to 30 years. After mating, she will return to her burrow to lay roughly 100 to 150 eggs, of which about two will make it to adulthood.

Tarantulas play a crucial role in their ecosystem acting as biological controls of insect populations, and as a source of food for other creatures such as mammals, lizards, birds and wasps. Tarantulas typically lie motionless by their burrows when hunting, waiting for the opportune moment to grab their prey and deliver a venomous bite. The venom will paralyze their prey, while they secrete a digestive enzyme that liquifies their meal so they can suck their food up through their straw-like mouth opening.

Despite their hunting prowess, tarantulas can also be an easy meal for larger predators. A tarantula’s primary defense mechanism is the barbed hairs on the back of their abdomen. It can shoot these hairs in the eyes and mucous membranes of its tormenter in hopes of scurrying away while the predator is distracted. The most feared predator of a tarantula is the large black and orange female tarantula hawk wasp (Pepsis sp.). This imposing insect seeks out tarantulas during late summer. When she locates a tarantula, the wasp attacks and delivers a paralyzing sting underneath the spider’s leg. The wasp then drags the tarantula to a hole and lays a single egg inside the tarantula before covering it. Once the larva hatches it will begin to feed on the still living tarantula, avoiding vital organs, which keeps its host alive and fresh.

However, predators like the tarantula hawk wasp are not the only scary threats to tarantulas—humans can be too! Human threats to tarantulas include cars, habitat destruction, and collection. It is illegal in many parks (including Mount Diablo) to collect tarantulas as pets. So, if you see one out and about, feel free to observe it but let it continue to play its important role in the local ecosystem.